VIEW FROM THE STREET

WHOSE STREETS? OUR STREETS!

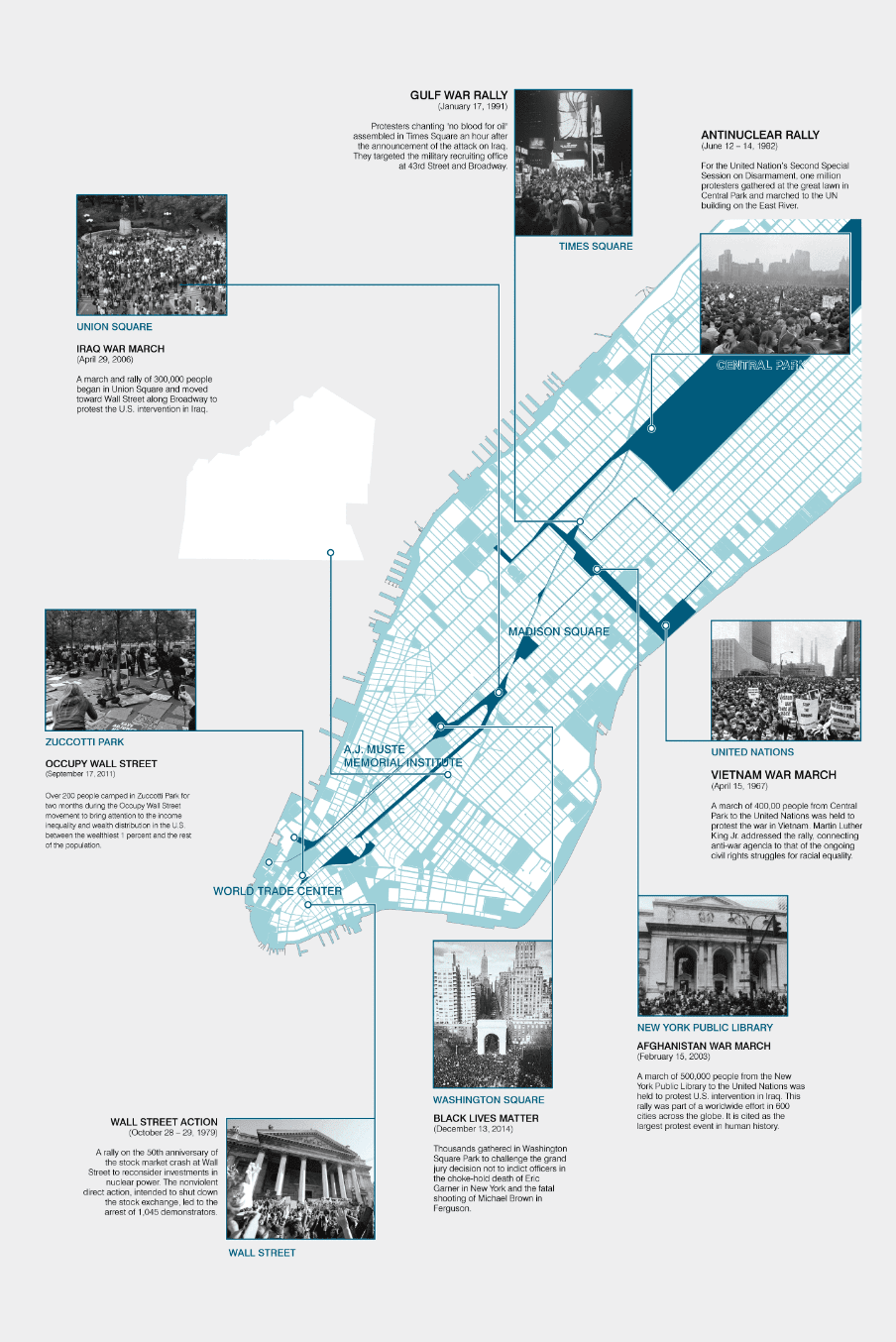

If the “powers that be” reside in marble halls and boardrooms, revolutions are born on the street. In the open air of the city, resistance can take the form of planned acts of civil disobedience or incidences of spontaneous protest. With impromptu crowds, militant marches, and dynamic performances, grassroots movements in the Lower East Side and elsewhere have commandeered public space in order to draw attention to a shared political cause, target repressive institutions, and demonstrate the coherence and extent of their popular support.

Familiar chants ring out: “Whose streets? Our streets!” “Show me what democracy looks like! This is what democracy looks like!” Even as the sound invites onlookers to join a newly visible public, these declarations bring implicit power struggles to the surface, provoking and escalating combat with the state. Throughout the political history of the Lower East Side, citizens have

Familiar chants ring out: “Whose streets? Our streets!” “Show me what democracy looks like! This is what democracy looks like!” Even as the sound invites onlookers to join a newly visible public, these declarations bring implicit power struggles to the surface, provoking and escalating combat with the state. Throughout the political history of the Lower East Side, citizens have

strategically used public protest and performative resistance to anchor social movements in time and space, lending materiality and visibility to efforts that might otherwise seem diffuse or abstract. Harnessing such events to capture the attention of the media and broadcasting local issues to a national stage allows social movements to situate regional actions within a global context.

The view from the street refers to a tradition of pageantry that defamiliarizes everyday spaces in order to draw attention to the issues impacting our everyday lives. The timeline of visible actions celebrates the work of activists and artists who have labored side by side to create striking, unexpected, public presentations.

The view from the street refers to a tradition of pageantry that defamiliarizes everyday spaces in order to draw attention to the issues impacting our everyday lives. The timeline of visible actions celebrates the work of activists and artists who have labored side by side to create striking, unexpected, public presentations.