VIEW FROM ABOVE

LOWER EAST SIDE/LOISAIDA

A grand schoolhouse, the former PS 64/ El Bohio Community Center, spans the block between 9th and 10th streets. Behind it, a landscape of six-story tenement buildings stretches toward the East River, the Williamsburg Bridge just visible between the blocks of NYCHA housing.

The neighborhood depicted here — the Lower East Side — is a place where people live, work, go to school, and create community with one another. But it is also a site of struggle, where successive generations of working-class and immigrant families wised up to the raw deal offered them by the political and economic status quo. Most of the Lower East Side’s tenements, recognizable here by their iconic airshafts, were constructed at the end of the 19th century to accommodate waves of immigrants from Europe. Seeking work and prosperous new beginnings in the thriving ports and small factories of lower Manhattan, newcomers instead found widespread corruption, exploitative employers, and profiteering landlords.

The neighborhood depicted here — the Lower East Side — is a place where people live, work, go to school, and create community with one another. But it is also a site of struggle, where successive generations of working-class and immigrant families wised up to the raw deal offered them by the political and economic status quo. Most of the Lower East Side’s tenements, recognizable here by their iconic airshafts, were constructed at the end of the 19th century to accommodate waves of immigrants from Europe. Seeking work and prosperous new beginnings in the thriving ports and small factories of lower Manhattan, newcomers instead found widespread corruption, exploitative employers, and profiteering landlords.

Today, vestiges of these Counter Institutions remain. But as speculation has made space in Manhattan’s lower wards harder to afford and life in gentrifying neighborhood harder for working-class communities to sustain, many of the movements born here have moved on to other neighborhoods. Yet, the history of the movements embedded in the Lower East Side is a reminder of the importance of space to organization.

These experiences gave rise to an alternative political vision, which found a home in religious, secular, and anarchist “Counter Institutions” throughout the Lower East Side. From labor unions and tenant associations to an assortment of neighborhood clubs and settlement houses, these Counter Institutions — as well as the buildings that housed them, and the people who stewarded them shaped the politics and culture for which the Lower East Side became known.

These experiences gave rise to an alternative political vision, which found a home in religious, secular, and anarchist “Counter Institutions” throughout the Lower East Side. From labor unions and tenant associations to an assortment of neighborhood clubs and settlement houses, these Counter Institutions — as well as the buildings that housed them, and the people who stewarded them shaped the politics and culture for which the Lower East Side became known.

Aerial view of the Lower East Side with El Bohio community center in the foreground, 2017.

Photograph by Gilbert Santana.

Photograph by Gilbert Santana.

PUBLIC HOUSING AND SETTLEMENT AS ESTABLISHMENT

As part of the well intentioned Settlement House activism, tenements that housed immigrants and generally considered unsanitary or lacking in quality of life, were demolished to make public housing in the Lower East Side.

In 1935, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia directed the New York Housing Authority (NYCHA) to begin working on proposals to build new low-income housing on various sites across New York City, which were financed by New Deal federal grants. Slum clearance and urban renewal made way for the new low-income, mid-rise housing along the Lower East Side’s waterfront.

![]()

![]()

In 1935, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia directed the New York Housing Authority (NYCHA) to begin working on proposals to build new low-income housing on various sites across New York City, which were financed by New Deal federal grants. Slum clearance and urban renewal made way for the new low-income, mid-rise housing along the Lower East Side’s waterfront.

Photograph shows neighborhood housing advocates with Henry Street director Helen Hall (center) waiting to board a bus from the Henry Street Playhouse to Washington DC to canvas for low-income housing on the L.E.S.

Photograph courtesy Social Welfare History Archives.

Photograph courtesy Social Welfare History Archives.

Photograph shows a group of boys and the advocates from Henry Street Settlement outside a Mobilization for Youth (MFY) rebuilding project.

Photograph courtesy Social Welfare History Archives.

Photograph courtesy Social Welfare History Archives.

Settlement House leaders actively supported this housing, which would prioritize the former tenants of demolished tenements, alongside newcomers including war veterans, African Americans and Puerto Ricans.

Some occupants of the housing viewed the Settlements’ methods of organizing and support as patriarchal and archaic.

As Settlement Houses became increasingly dependent on government support, the institutions became less radical in an effort to remain vital within the expanding bureaucracy of social welfare.

![]()

Some occupants of the housing viewed the Settlements’ methods of organizing and support as patriarchal and archaic.

As Settlement Houses became increasingly dependent on government support, the institutions became less radical in an effort to remain vital within the expanding bureaucracy of social welfare.

New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) blocks of housing along the East River built between 1940-1965, showing occupancy in 2019. Data collected from web-based NYCHA Interactive Map.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

MIGRANT ENCLAVE

Half a century after European immigrants came looking for prosperous new beginnings in the thriving port and small factories of lower Manhattan, Puerto Rican migrants followed in the footsteps of their Jewish, German, Irish, and Ukrainian predecessors.

Expressions of belonging on the LES changed after the 60s as Puerto Ricans and blacks had been ghettoized as the aggressors of their ‘self-induced poverty’ by a top down urban planning racial geography of ‘urban crisis’ also labeled as the “Puerto Rican Problem”. Earlier plans from the 50s to bring a digestible and assimilated Puerto Rican culture to the built environment had ceased. Yet, the radical consciousness of second generation Puerto Ricans -the largest migration demographic at the time- began to take the built environment of the Lower East Side into their own hands and to embrace the once pejorative term Nuyorican to create a new a hybrid identity that rebranded the neighborhood with the spanglish term Loisaida.

Much of it was spearheaded by the Real Great Society in the 60s, an activist group of rehabilitated Puerto Rican gang leaders (co-founded by Chino Garcia who later spinned -off into CHARAS) that served as a focal point of community innovation, energy and growth. Along with Adopt- A- Building, the groups demonstrated a community embarking upon the process of reclaiming and place-keeping that combated invisibility, created a sense of public belonging, and offered a blueprint to the eventual Young Lords formation and counter-institution building by Nuyorican poetry and arts movements.

Today The Clemente is one of the few remaining brick and mortar institutional legacies of Puerto Rican/ Latinx cultural activism remaining in Loisaida. Acting as a repository of memories not included enough in official archives, the cultural hub houses 4 theaters, 2 galleries, and 46 subsidized studios housing 70 plus resident artists and small arts organizations on the city-owned historic PS 160 that it stewards for future generations of creative beneficiaries. Its unique mission plays a critical and unusual role, providing deep affordability to emergent and mid-career cultural producers as well as its distinct programs, art commissions, cultural equity, and public humanities initiatives. The Clemente has spent three decades harnessing heterogeneity into strength, serving as a sanctuary space, and supporting communities on the ground, including communities of artists..

Expressions of belonging on the LES changed after the 60s as Puerto Ricans and blacks had been ghettoized as the aggressors of their ‘self-induced poverty’ by a top down urban planning racial geography of ‘urban crisis’ also labeled as the “Puerto Rican Problem”. Earlier plans from the 50s to bring a digestible and assimilated Puerto Rican culture to the built environment had ceased. Yet, the radical consciousness of second generation Puerto Ricans -the largest migration demographic at the time- began to take the built environment of the Lower East Side into their own hands and to embrace the once pejorative term Nuyorican to create a new a hybrid identity that rebranded the neighborhood with the spanglish term Loisaida.

Much of it was spearheaded by the Real Great Society in the 60s, an activist group of rehabilitated Puerto Rican gang leaders (co-founded by Chino Garcia who later spinned -off into CHARAS) that served as a focal point of community innovation, energy and growth. Along with Adopt- A- Building, the groups demonstrated a community embarking upon the process of reclaiming and place-keeping that combated invisibility, created a sense of public belonging, and offered a blueprint to the eventual Young Lords formation and counter-institution building by Nuyorican poetry and arts movements.

Today The Clemente is one of the few remaining brick and mortar institutional legacies of Puerto Rican/ Latinx cultural activism remaining in Loisaida. Acting as a repository of memories not included enough in official archives, the cultural hub houses 4 theaters, 2 galleries, and 46 subsidized studios housing 70 plus resident artists and small arts organizations on the city-owned historic PS 160 that it stewards for future generations of creative beneficiaries. Its unique mission plays a critical and unusual role, providing deep affordability to emergent and mid-career cultural producers as well as its distinct programs, art commissions, cultural equity, and public humanities initiatives. The Clemente has spent three decades harnessing heterogeneity into strength, serving as a sanctuary space, and supporting communities on the ground, including communities of artists..

Map of Puerto Rico.

Map of Puerto Rico and New York City showing enclaves of Puerto Rican settlement.By 1960, over 600,000 people of Puerto Rican birth or parentage lived in NYC.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

The Clemente’s facade

Aerial view of the Lower East Side with The Clemente / PS 160 building in the foreground, 2017.

Photograph by Gilbert Santana.

Photograph by Gilbert Santana.

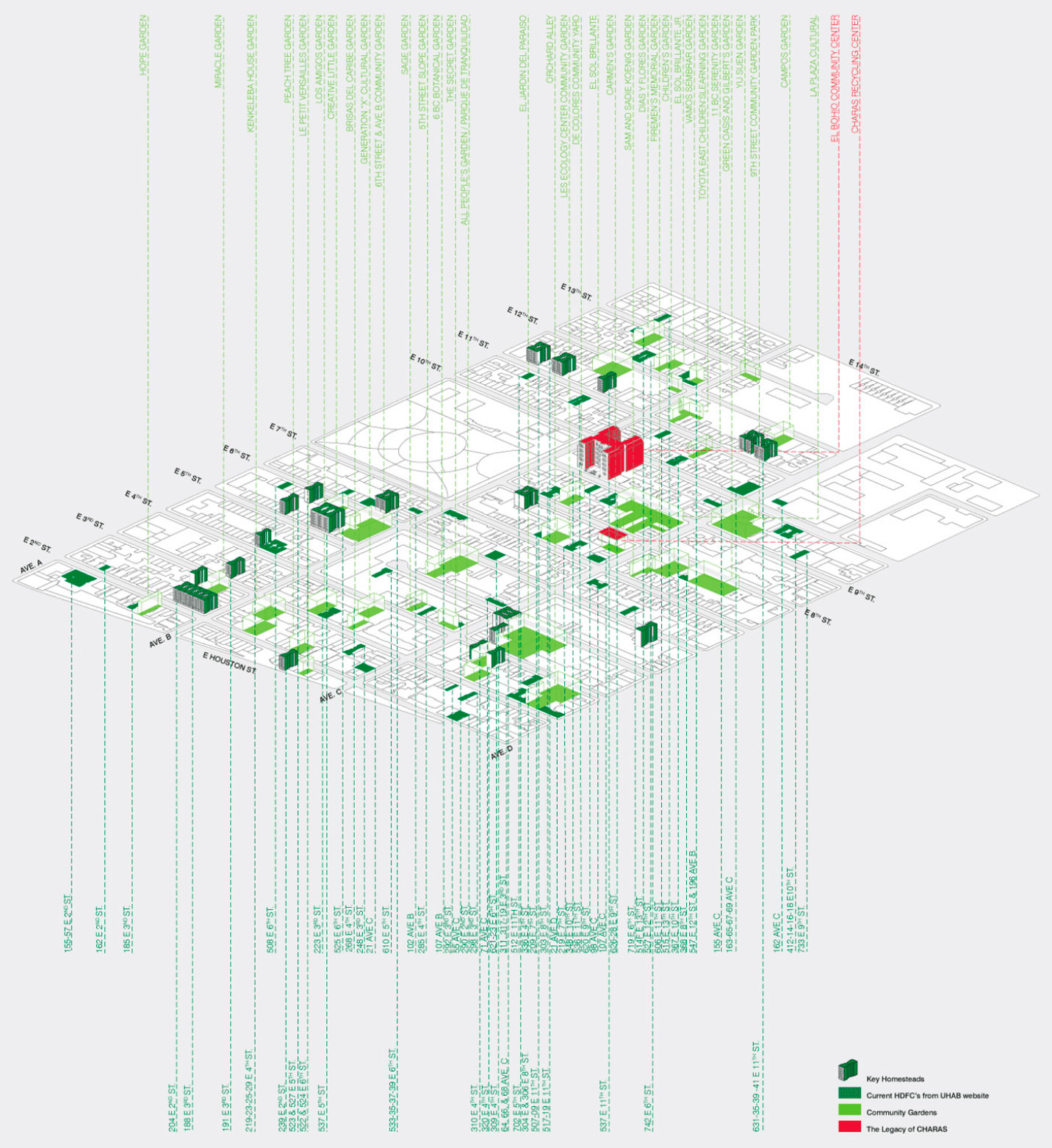

HOMESTEADS AND GARDENS

While squatting/ rent strikes have a long history, Urban Homesteading was officially recognized by the federal government in 1974. It was a grassroots movement organized by tenants and housing advocates to renovate abandoned/ poorly managed tenement housing into cooperatively owned housing. Through a process of sweat equity, future owners of the apartments fixed the buildings themselves. Given the rampant demolition and destruction of tenements in the 70’s during the city’s famous bankruptcy, a Do It Yourself spirit became an integral part of the culture. In parallel, the enactment of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), which federally employed more than 10,000 artists – visual, performing, and literary – between 1974-1981, also played a role reinforcing the vigor of public service and cultural organizing directly connected to the community garden, casitas, and community mural movement which flourished in the neighborhood.

Through alliances with sectors, Puerto Rican and LES activist artists not only started numerous community gardens, but explored alternative energy sources and recycling centers, linking environmental and ecological issues to that of neighborhood revival. Their pragmatic and ecological undertakings enacted a cultural citizenship through public activities that demonstrated a community embarking upon the process of placemaking which pre-figured the birth of the city’s urban homesteading movement.

City and federal agencies looked to local housing advocacy groups to provide the infrastructure and community outreach to make these projects viable, and to provide the tenants with the technical assistance necessary to self-manage a building long-term. Once the homestead proved to be under a stable internal management structure, the apartments were transferred from the agency to the resident homesteaders as limited equity cooperatives.

By the 1990’s community gardens had a precarious existence but as a result of the community resistance many survived the moment when mayor Rudolph Giuliani targeted the gardens for auctioning off city properties. These spaces were social experiments that to this day create their own reality, and in which gardening equated a cultural activism of vernacular architecture (Casitas) and political resistance. The gardens and the homesteads (still in existence as limited equity housing) are proof that communities are capable stewards of land and property.

Through alliances with sectors, Puerto Rican and LES activist artists not only started numerous community gardens, but explored alternative energy sources and recycling centers, linking environmental and ecological issues to that of neighborhood revival. Their pragmatic and ecological undertakings enacted a cultural citizenship through public activities that demonstrated a community embarking upon the process of placemaking which pre-figured the birth of the city’s urban homesteading movement.

City and federal agencies looked to local housing advocacy groups to provide the infrastructure and community outreach to make these projects viable, and to provide the tenants with the technical assistance necessary to self-manage a building long-term. Once the homestead proved to be under a stable internal management structure, the apartments were transferred from the agency to the resident homesteaders as limited equity cooperatives.

By the 1990’s community gardens had a precarious existence but as a result of the community resistance many survived the moment when mayor Rudolph Giuliani targeted the gardens for auctioning off city properties. These spaces were social experiments that to this day create their own reality, and in which gardening equated a cultural activism of vernacular architecture (Casitas) and political resistance. The gardens and the homesteads (still in existence as limited equity housing) are proof that communities are capable stewards of land and property.

Homesteads, gardens, and the legacy of CHARAS/El Bohio Community Center.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.