VIEW FROM WITHIN

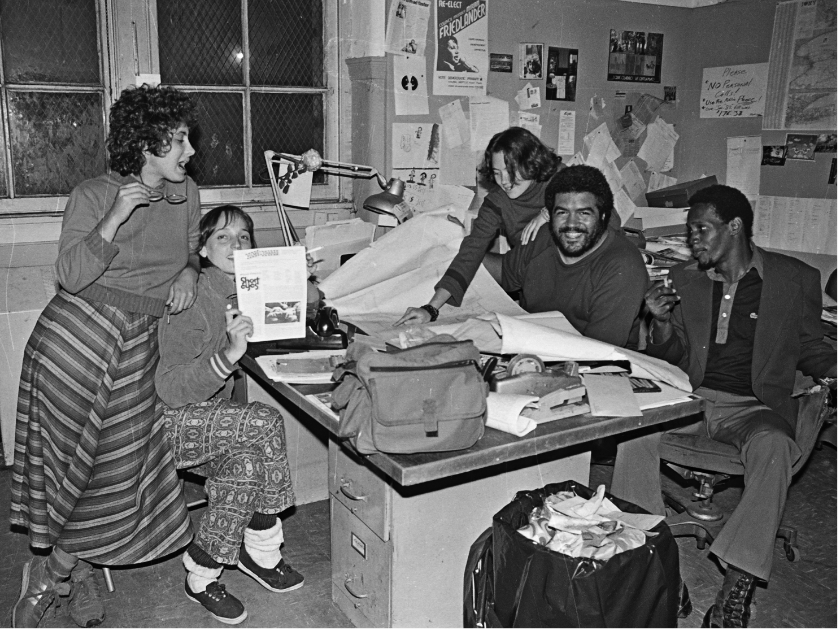

REVOLUTION FROM WORK DESKS

The office buildings, churches, settlement houses, galleries, and co-ops that house the resistance movements in Loisaida materially represent the conceptual struggle to create space for civic action in a city driven by real estate. In the ’70s, a temporary dip in property values, allowed renegade Lower East Siders to claim physical spaces in whic popular movements could take root and flourish.

From the war resisters at the Peace Pentagon to Puerto Rican community organizers at El Bohio, to the anarchist punks at ABC No Rio, the longevity and effectiveness of social organization has depended on a stable headquarters sheltered from the vagaries of the market. Counter Institutions require space in which to plan, organize, and build a culture of creative resistance that keeps democracy alive.

From the war resisters at the Peace Pentagon to Puerto Rican community organizers at El Bohio, to the anarchist punks at ABC No Rio, the longevity and effectiveness of social organization has depended on a stable headquarters sheltered from the vagaries of the market. Counter Institutions require space in which to plan, organize, and build a culture of creative resistance that keeps democracy alive.

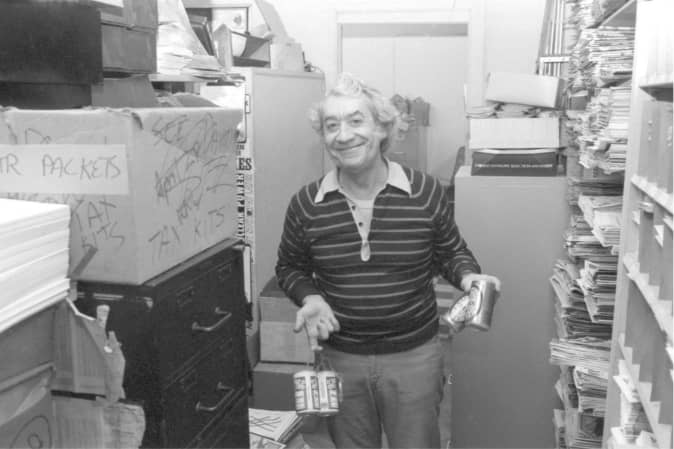

The view from within refers to the interior where generations of activists have collaborated and argued to shape popular resistance. Whether broadcasting against government misinformation, stuffing envelopes and planning marches, or hosting spoken word performances, the activities that take place within the walls of these “Activist Estates” relies on an ethic of solidarity and DIY voluntarism.

These building interiors often invisible from the outside serve as second homes to the organizers and artists who work within them and foster comradery. While the city trends towards privatization, the lopsided floors, vibrant decor, and make-shift infrastructures of these buildings enshrine an anarchic and inclusive domesticity.

These building interiors often invisible from the outside serve as second homes to the organizers and artists who work within them and foster comradery. While the city trends towards privatization, the lopsided floors, vibrant decor, and make-shift infrastructures of these buildings enshrine an anarchic and inclusive domesticity.

Collectively, these tenacious spaces stand against the marginalization that threatens the working-class majority who calls this city home.

Films

Operation Class War on the Lower East Side

Paper Tiger Television, 1992.

A 28 minute video by Paper Tiger Television with highlights complains Square Park, the homeless problem of the neighborhood, the riot of 1988, and the events leading to the closure of the park. An exposing look at the local mainstream media, NYC government, police and developers. With local radio, video, and community activists.

Home(less) Is Where The Revolution is

Paul Garrin 1990.

In Homeless, Garrin combines the high tech with the lo-fi to create a hyper-rela landscape of confrontation using the power of technology to drop homeless squatters onto the lawn of the White House in a hard-hitting inversion of the power struggle.

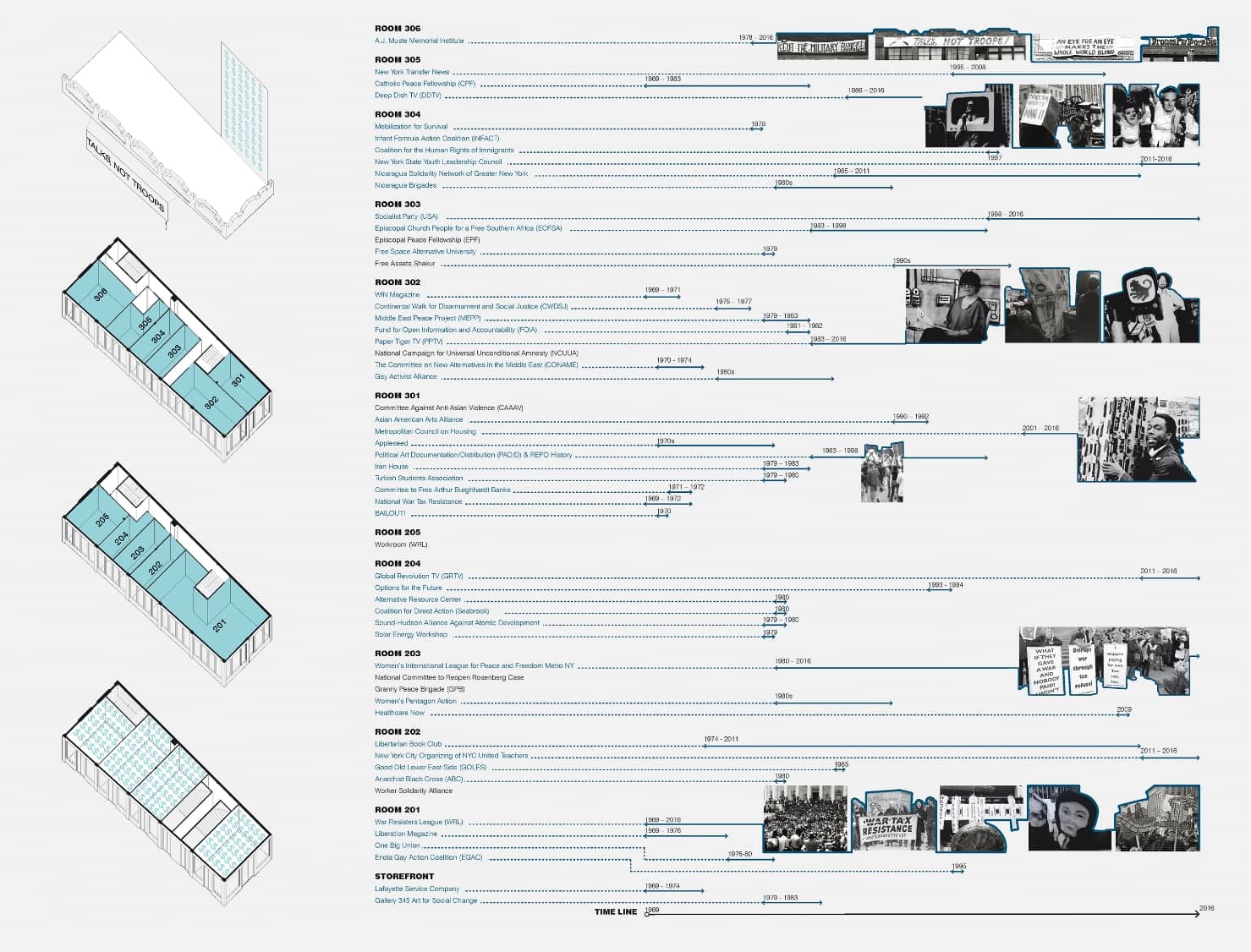

Timeline of occupants, their rooms, and their actions at the Peace Pentagon, 1969-2016. Tenant list compiled with the assistance of Ed Hedemann. Past tenants, correspondence, newsletters, and meeting notes from A.J. Muste Memorial Institute.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

The peace pentagon

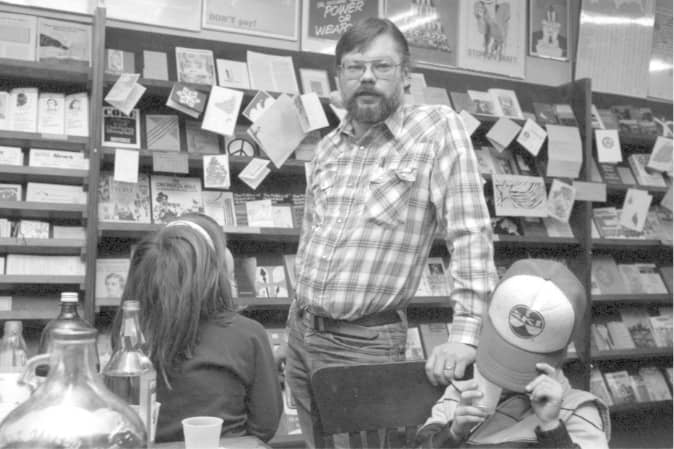

By leasing offices across three floors of 339 Lafayette Street to their anti-war allies at subsidized rates, the WRL and the Muste Institute cultivated ideological and financial collaboration and established a de facto headquarters for the radical peace and justice movement in New York City. The first generation of activists worked interchangeably on the various peace and social justice projects initiated by the WRL. But in later years, new “movement tenants” brought a focus on anti-nuclear, anti-apartheid, feminist, and environmental concerns to the Peace Pentagon. They came seeking congenial workspace and low rents. The strategic and ideological convictions of these new tenants were sometimes in conflict, but all shared a fundamental belief in social change through nonviolent action.

The beloved community

Once the vibrant center of an empowered working class, by the 1970s, the neighborhood surrounding the Peace Pentagon had become a catchment area for the city’s disenfranchised and destitute. Auto body shops and hardware supply stores provided some semblance of commercial activity along Lafayette Street during the day. But by night, homeless people, many struggling with drug and alcohol addiction and mental illness, flocked to the Bowery looking for shelter. Long known for its homeless shelters, soup kitchens, and other charitable institutions, the Bowery became the epicenter of an emerging homelessness crisis in 1970s New York.

The “Peace Pentagon” at the corner of Lafayette

and Bleecker Streets, 1978.

photograph by David McReynolds.

photograph by David McReynolds.

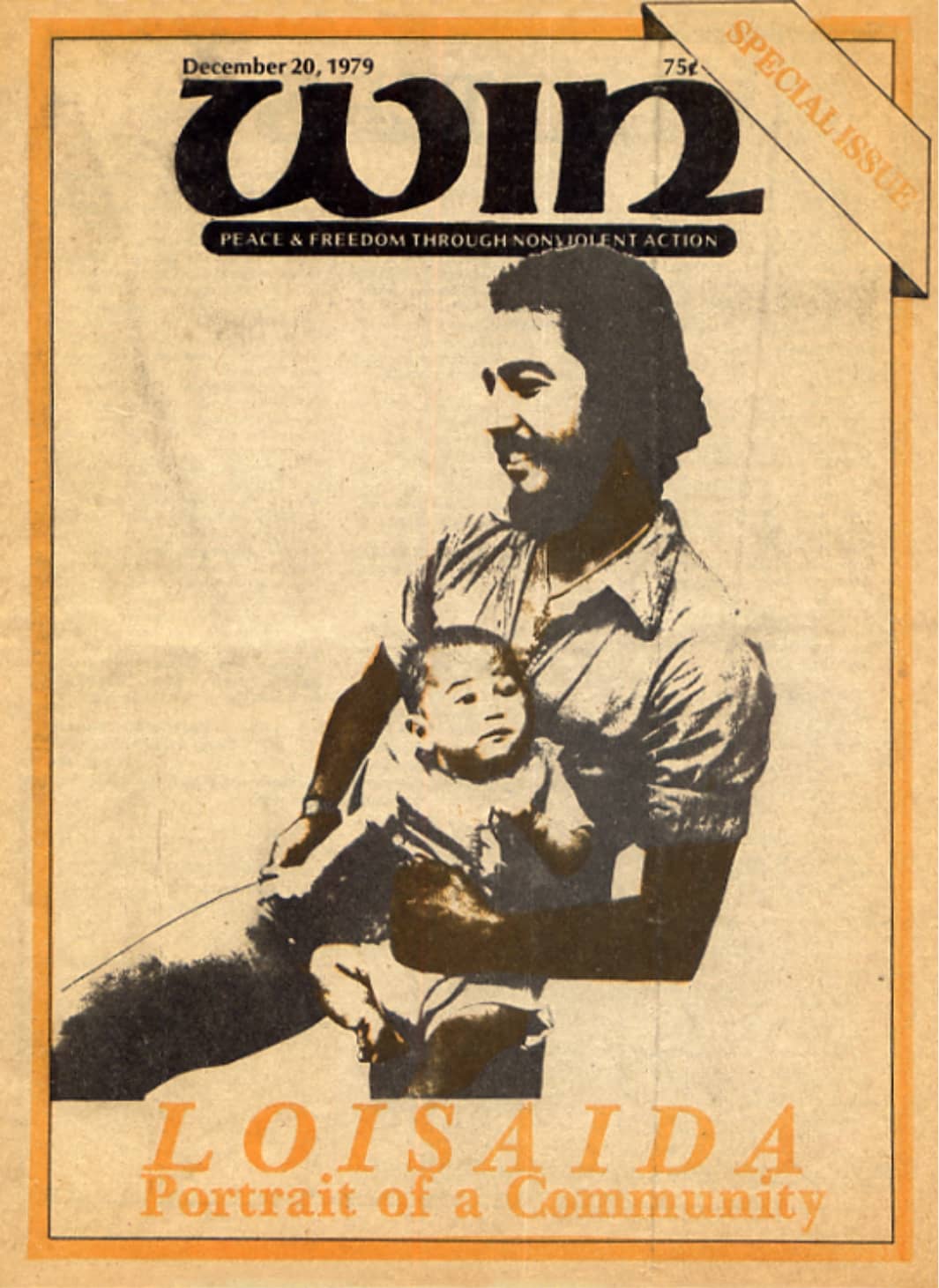

Loisaida Movement featured within, and on the cover of war resisters’ WIN Magazine. December 20, 1989.

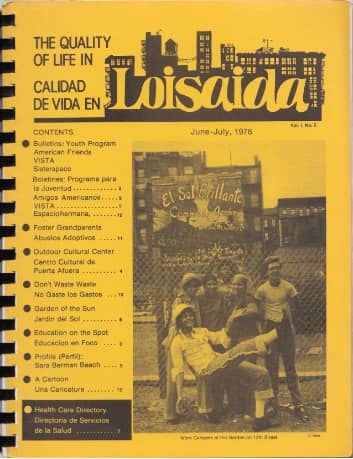

Quality of Life in Loisaida, Bilingual Magazine.

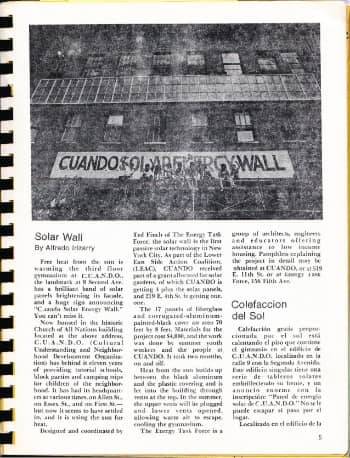

Excerpts of the Alternate Technology Movement, Courtesy of Loisaida Inc.

El milagro de loisaida

In June 1978, WIN Magazine, which typically covered war, peace, and nonviolent action, dedicated an entire issue to “Loisaida”. An editorial noted that “the people of Loisaida have risked voicing their lives to an unknown audience, stepping beyond the boundaries of their neighborhood to speak to their sisters and brothers in the nonviolent left.” Other articles focused on Loisaida activists’ struggles and accomplishments in the realms of housing, environmental initiatives, poetry, music, and performance.

In June 1978, WIN Magazine, which typically covered war, peace, and nonviolent action, dedicated an entire issue to “Loisaida”. An editorial noted that “the people of Loisaida have risked voicing their lives to an unknown audience, stepping beyond the boundaries of their neighborhood to speak to their sisters and brothers in the nonviolent left.” Other articles focused on Loisaida activists’ struggles and accomplishments in the realms of housing, environmental initiatives, poetry, music, and performance.

Section cutaway of 519 E 11th street showing solar collectors on the roof and energy conservation. Energy Task Force, Windmill Power for City People: A documentation of First World Urban Wind Energy System, New York City, 1977.

The publicity generated by such coverage drew allies and collaborators to Loisaida. A group of young architects, experimenting with small-scale alternative energy-generation technologies within new models of affordable housing, set up an “Energy Task Force” in a pilot homestead building at 519 East Eleventh Street. After adding improved insulation and solar collectors to reduce operating costs, the group upped the ante by collaborating with the homesteade

![]()

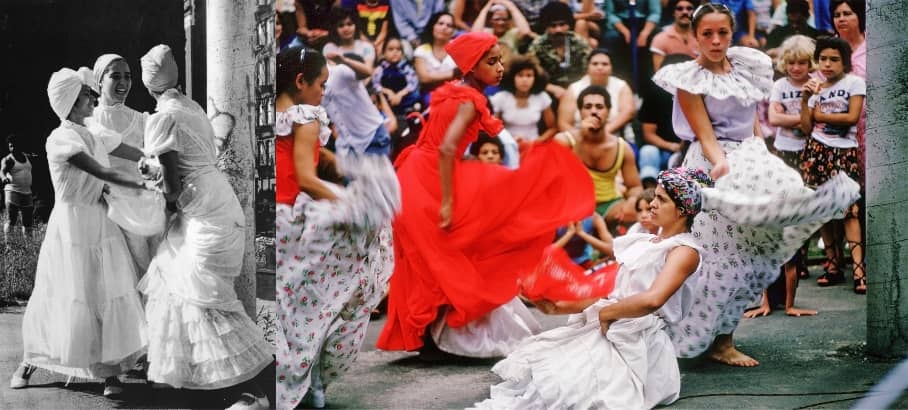

Grupo Cemi performs in La Plaza Cultural, 1980

Photograph by Marlis Momber.

Photograph by Marlis Momber.

Sweat equity and housing

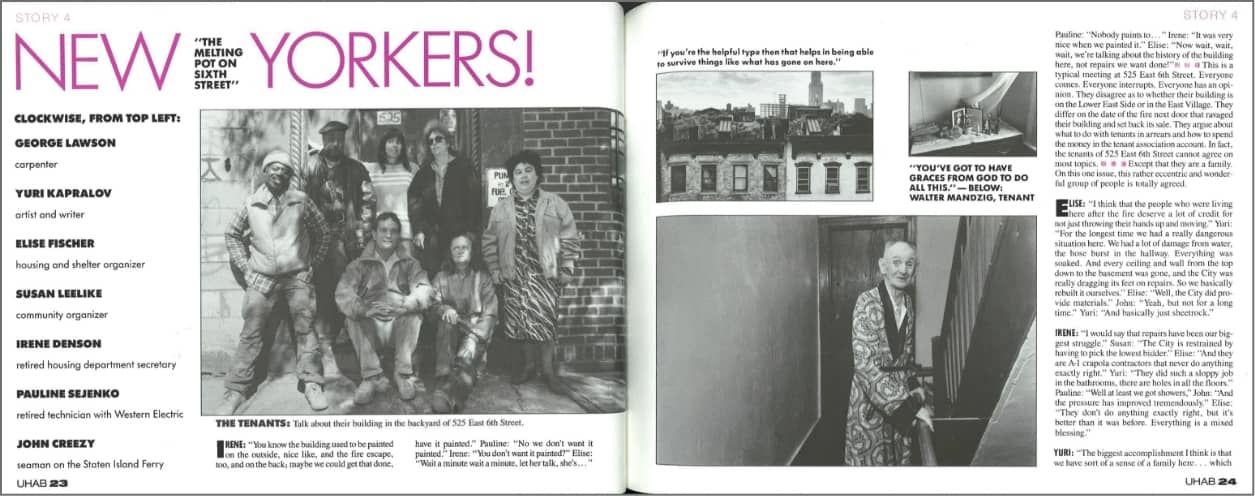

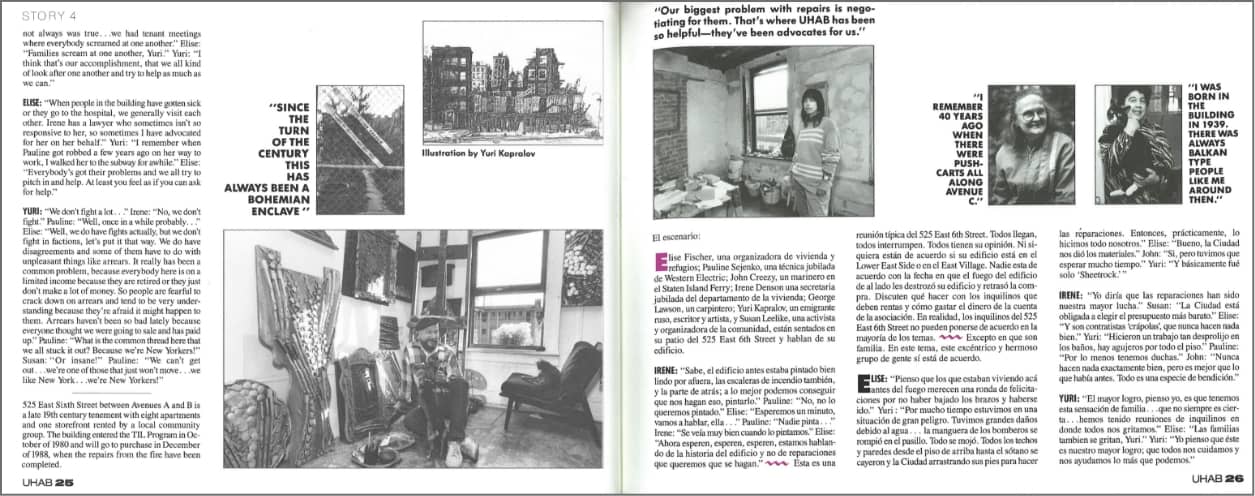

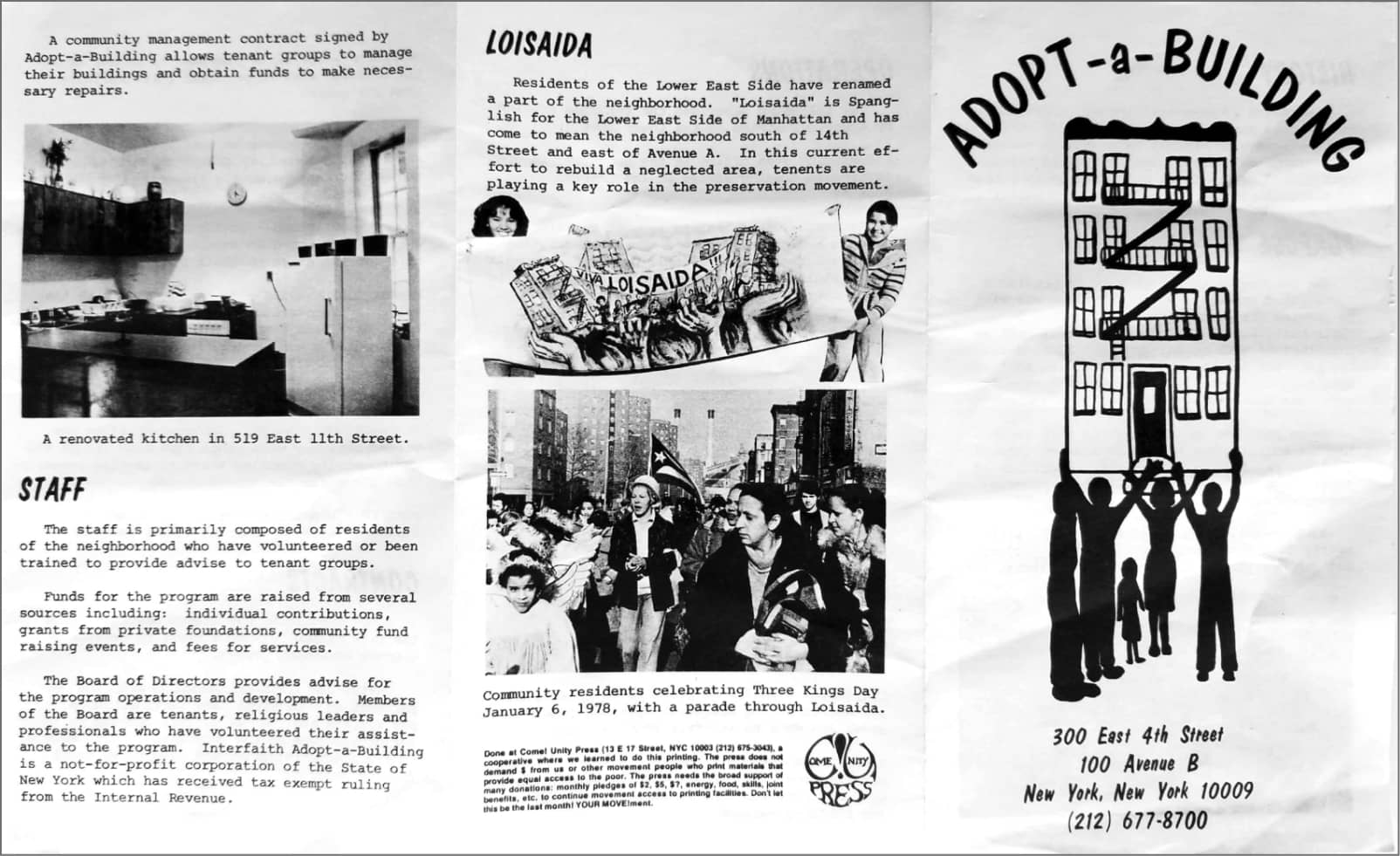

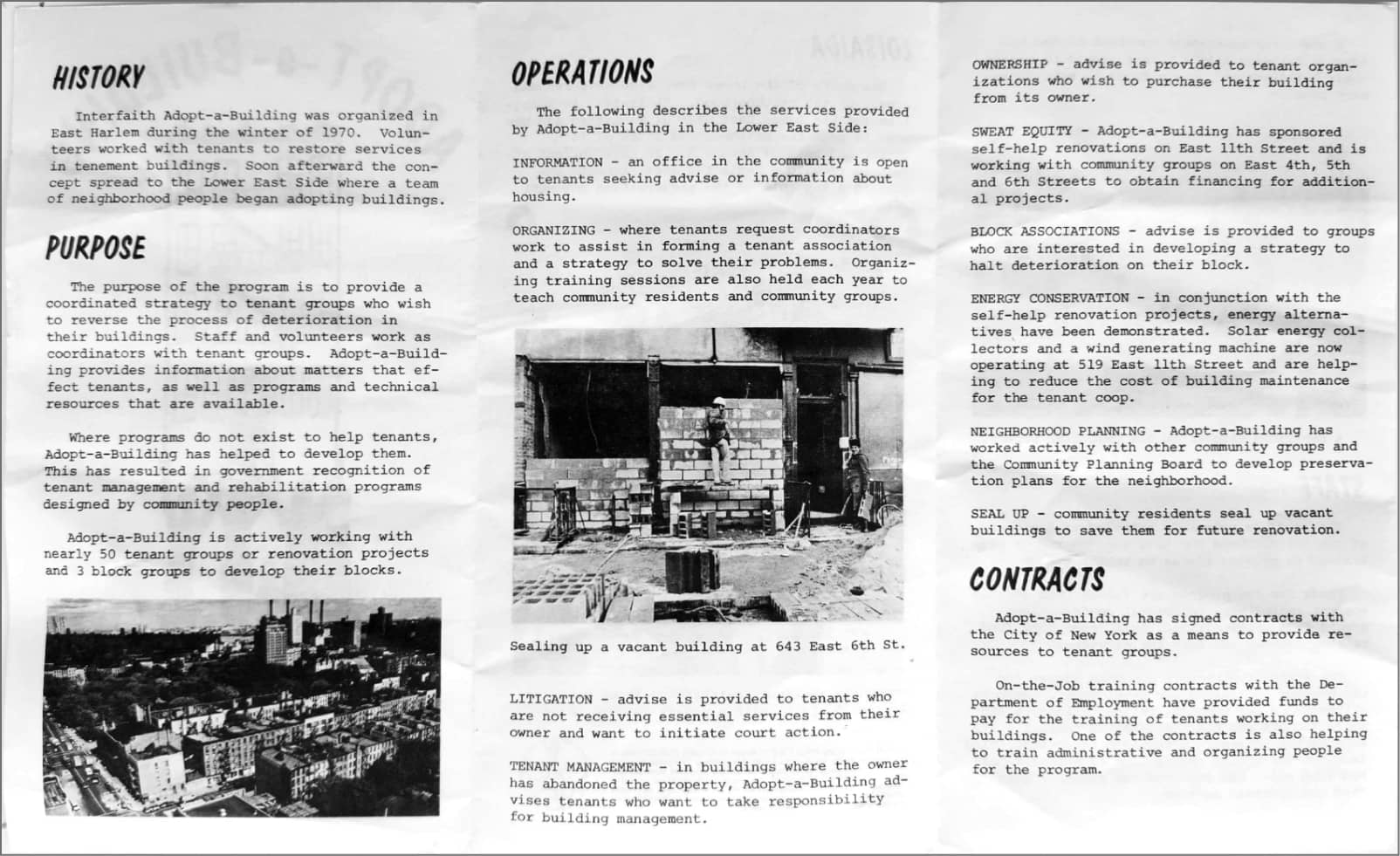

Housing advocacy groups such as Adopt-A-Building and the Urban Homesteading Board Assistance Board (UHAB) brought sweat equity housing to Loisaida. The New York City Department of Housing, Preservation, and Development (HPD) saddled with unwanted real estate in need of repair and upkeep looked favorably on homesteading. — through which people invested labor to fix up a property, and thus secured a stake in its future occupancy —. In Loisaida, radicals, housing advocates, church congregations, and ordinary citizens alike were drawn both to homesteading’s ideological. Rich in its ideological dimensions (the de-commodification of labor, the hard work involved, and the bottom-up ethic) and practical benefits (warm homes with limited equity.), this movement attracted a large cast of characters.

Key homesteaded buildings in Loisaida, 1974-1991.

List compiled from different sources, including the research by Malve von Hassell

“Homesteading in New York City, 1978-1993: The Divided Heart of Loisaida” (1996). Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

Inside TIL / Descubriendo TIL.

The idea of putting apartments back into tenants’ hands seems simple. But implementation was a long and complex process, beginning with assembling construction crews, negotiating construction loans, and harnessing the labor of future residents, many of whom were unskilled. At a minimum, the buildings had to be up to code and habitable, but the agencies’ long-term goal went even further: Buildings had to be financially and organizationally secure in order to pay back their loans. Housing advocacy groups created the community infrastructure to make these projects viable and provided tenants with the technical assistance necessary to self-manage their buildings. Only once a homestead possessed a stable internal management structure were the apartments transferred from the agency to the resident homesteaders as limited equity cooperatives.

In Our Self Own Help Words. UHAB 1974-1988

Adopt-a-Building brochure, 1979.

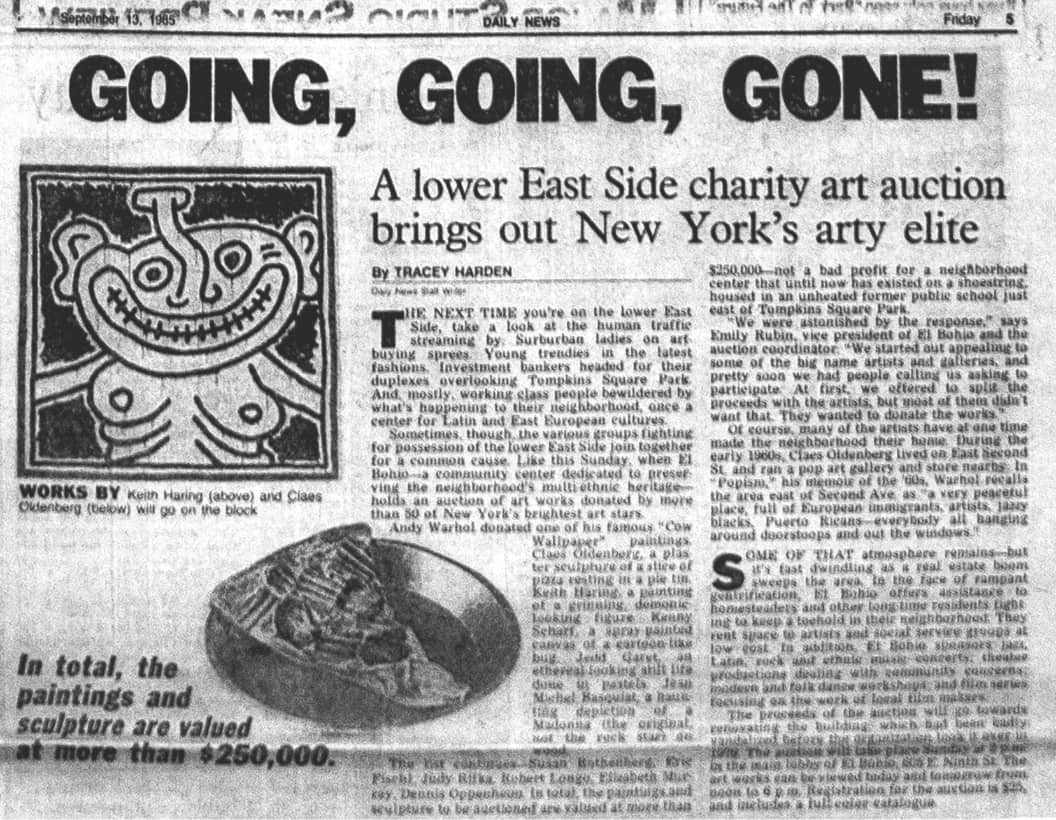

ART AT EL BOHIO

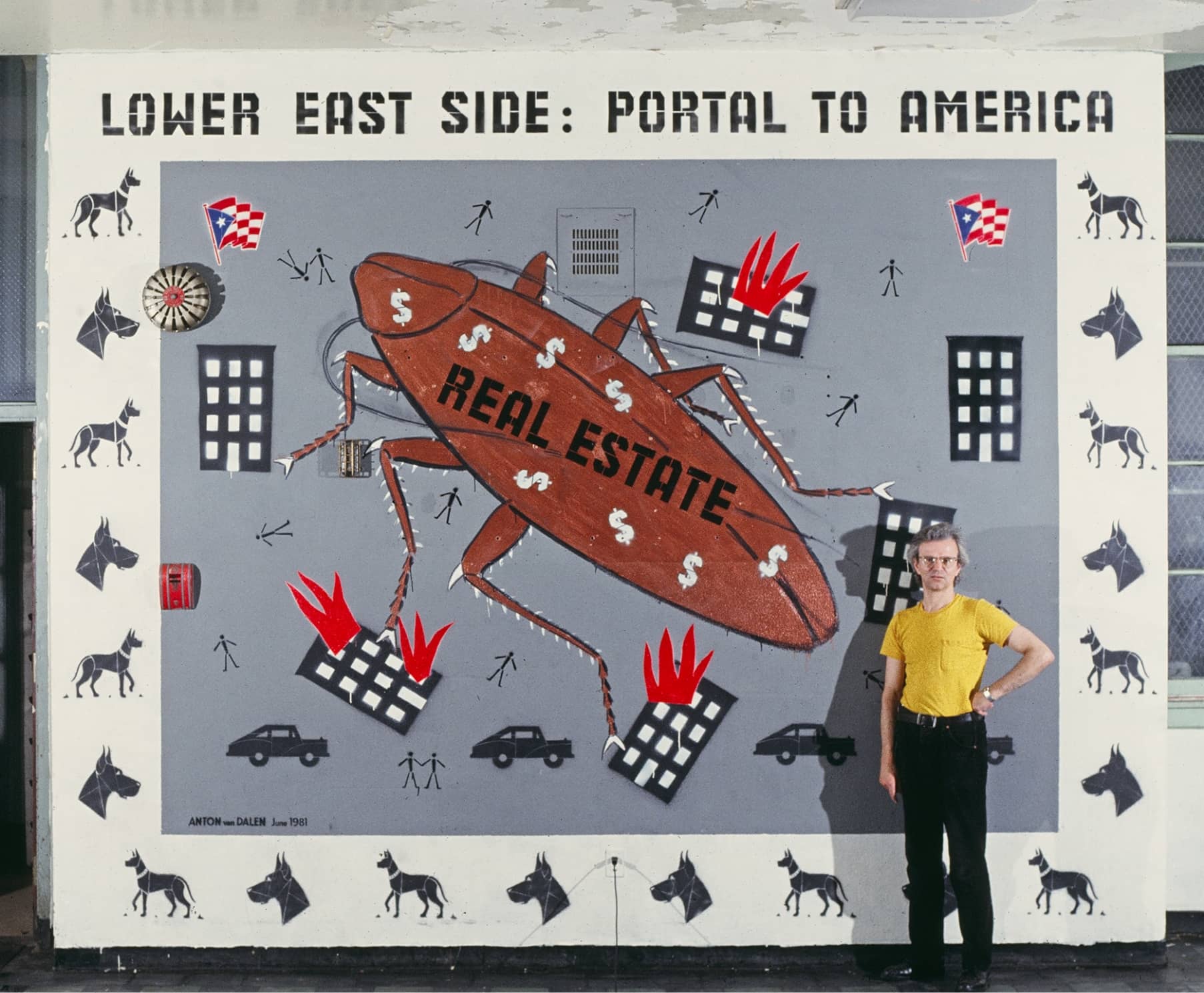

Among the early operatives within the El Bohio Community Center, Steven Loaves Inc., a nonprofit art coalition, supported smaller arts collectives including Children Arts Workshop, Printshop, Fourth Street I, Cityarts, Los Hispanos, and Teatro Ambulante. In the 80s El Bohio became a community-run arts and exhibit venue, simultaneously connecting to a new, vibrant art scene and promoting artists of color. The walls of the building’s Ninth Street lobby were cleaned, painted, and fitted with lighting; performances of jazz and Latin music, as well as a makeshift bar, enlivened openings at the gallery space. In 1980, El Bohio presented part of a large group show on nuclear disarmament, sponsored by the collective Artists for Survival. On the southern wall inside the gallery, a floor-to-ceiling mural by Anton Van Dalen focused attention on local housing problems by depicting the neighborhood with a giant cockroach labeled “Real Estate” at the center. Many of the artistic projects at El Bohio reflected the synergy between the housing, cultural, and environmental movements in the neighborhood.

Artist Anton Van Dalen with his mural, Lower East Side: Portal to America, in the main lobby of El Bohio, 1981. Photograph by Linda Davenport, courtesy of Anton van Dalen.

News clip, Art Auction. Records of CHARAS El Bohio. Courtesy Centro Archives, Hunter College, CUNY.

Gallery / Lobby at El Bohio.

Photograph by Marlis Momber.

Photograph by Marlis Momber.

El Bohio Community Center sectional view whit select list of users and their locations within the building.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

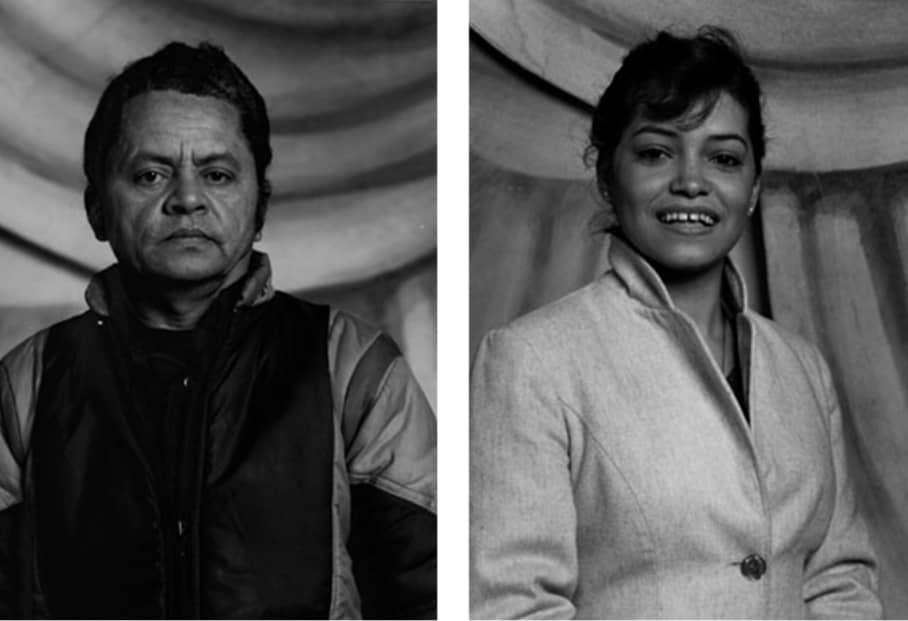

COMMUNITY AT EL BOHIO

In 1978, after helping residents of the Lower East Side establish control over poorly managed and abandoned apartment buildings, the housing advocacy group Interfaith Adopt-A-Building (A-A-B) was looking to adopt a building of its own. They set their sights on an abandoned schoolhouse, the former Public School 64, on a block adjoining Tompkins Square Park. Leveraging their connections with the city to gain access to the property, A-A-B invited CHARAS to join them in renovating, occupying, and running the large facility. The center was named El Bohio — “the hut” — to reflect the activism of the Puerto Rican community of the Lower East Side.

films and performance

AT EL BOHIO

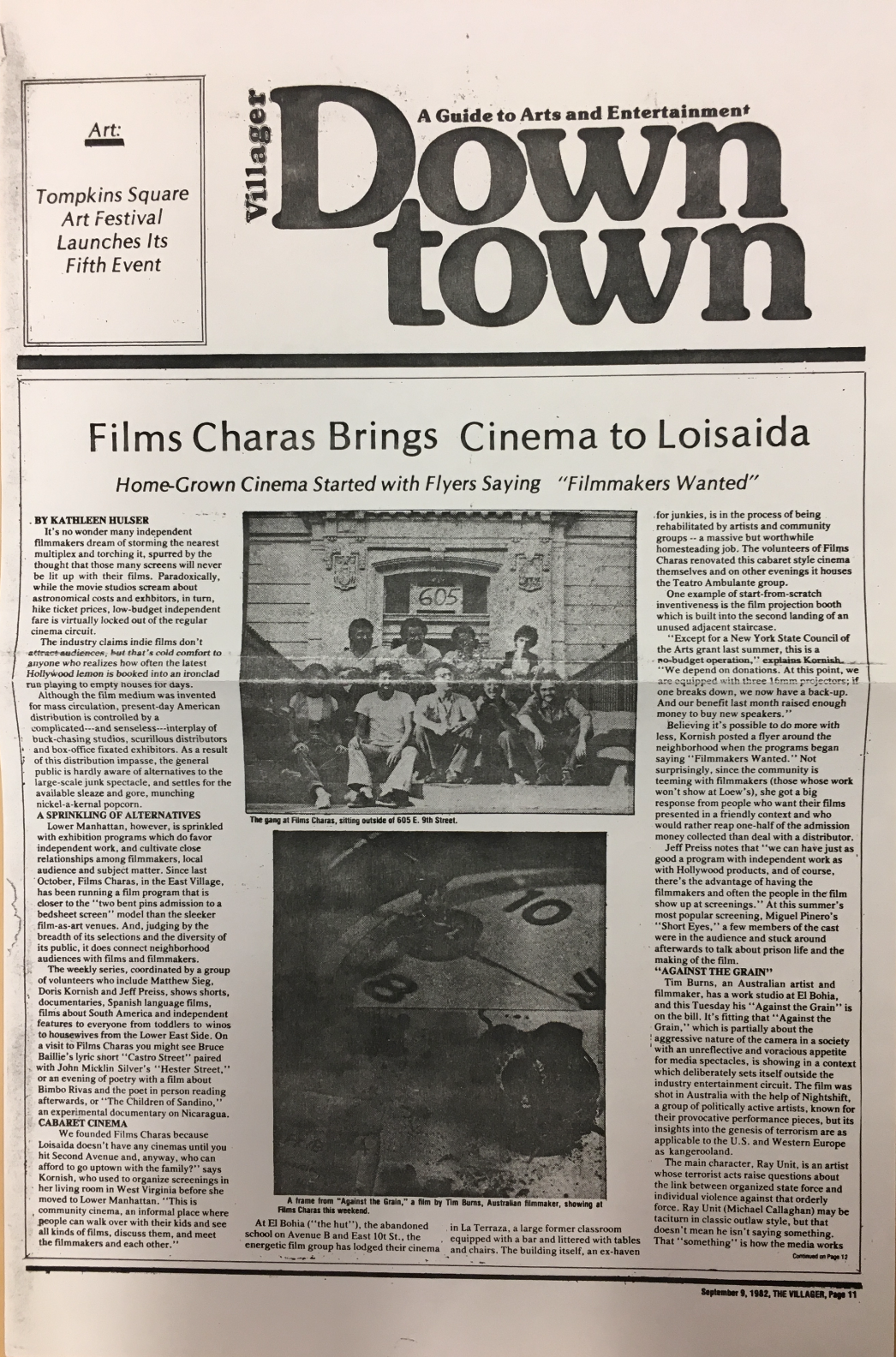

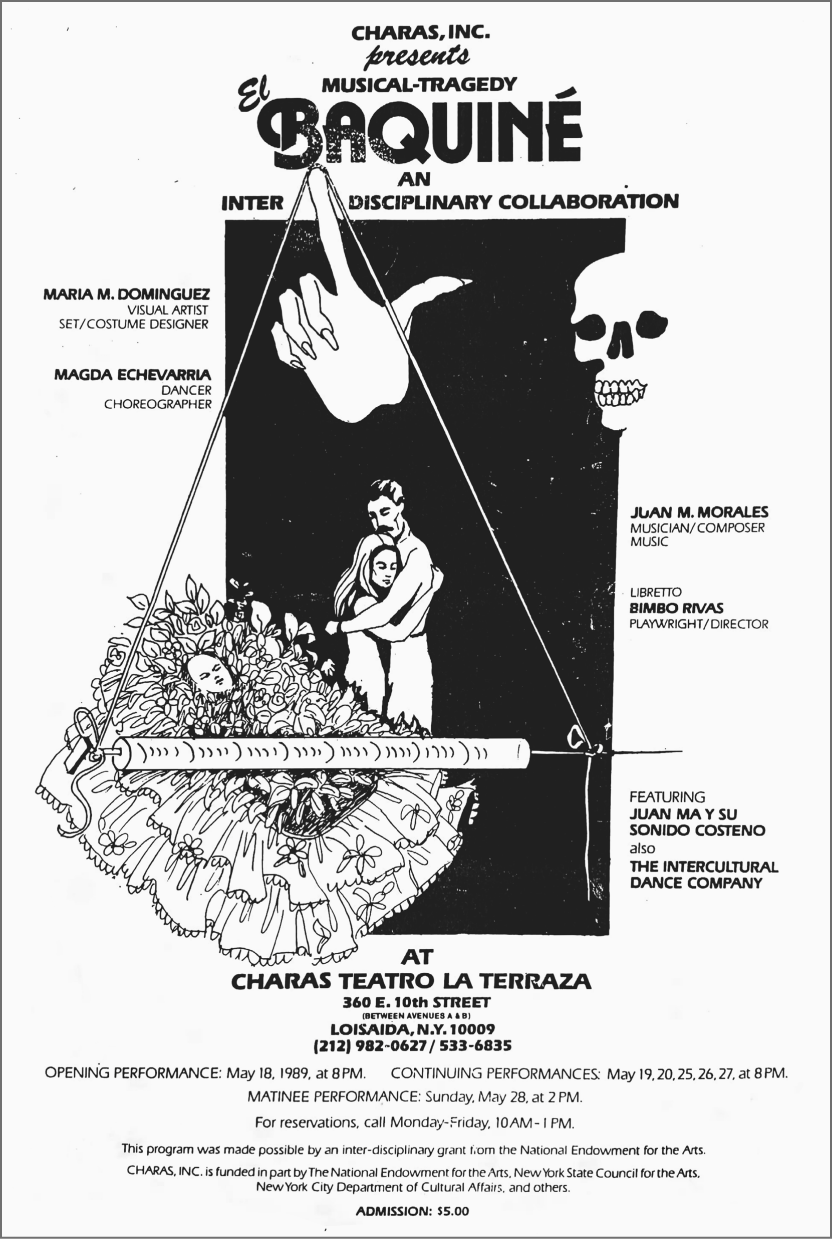

The many successful performances produced by CHARAS in the neighborhood’s parks and public spaces found a more permanent indoor venue in the renovated 350-seat auditorium in the basement of El Bohio. In 1981, the New Assembly Theater opened with Winos, a play by Bimbo Rivas about the problems of alcoholism and drug addiction within the community.

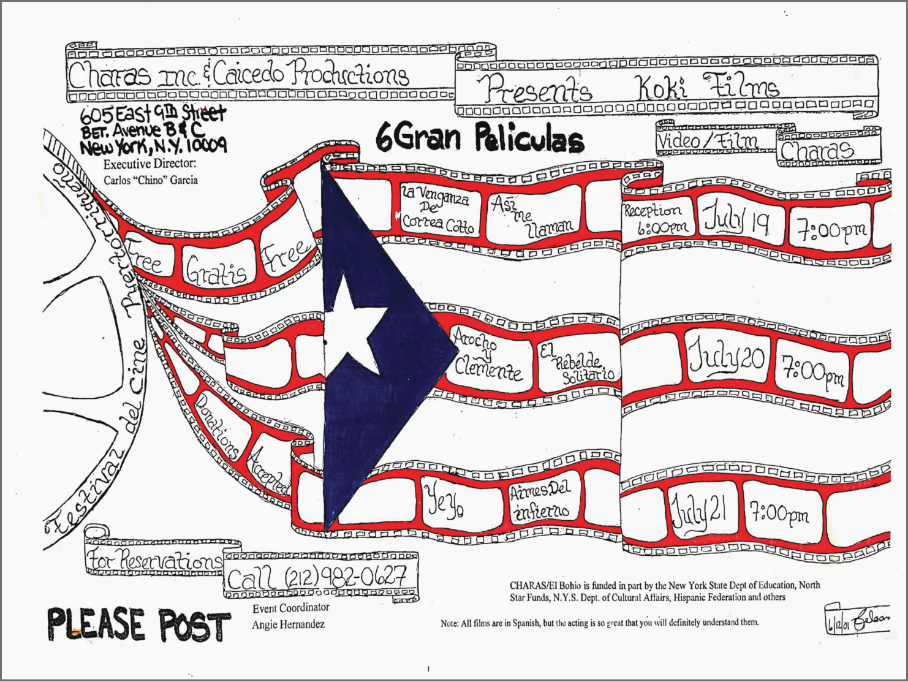

With the addition of a projection booth, the building’s old cafeteria became a film venue. Films CHARAS highlighted politically-themed films and invited young, relatively unknown film makers such as Spike Lee to present their work. Classic films were paired with the lesser-known filmmakers from Latin America, Africa, and Asia, to explore transnational themes of struggle against capitalism, war, and poverty, while conversations with filmmakers encouraged audience participation. Attractively designed posters pasted around the neighborhood advertised the series, and Films CHARAS soon became a Loisaida institution.

Newsclip, Film CHARAS.

Records of CHARAS El Bohio. Courtesy Centro Archives, Hunter College, CUNY.

CHARAS Theater Posters.

Records of CHARAS El Bohio. Courtesy Centro Archives, Hunter College, CUNY.

Films CHARAS Posters.

Records of CHARAS El Bohio. Courtesy Centro Archives, Hunter College, CUNY.

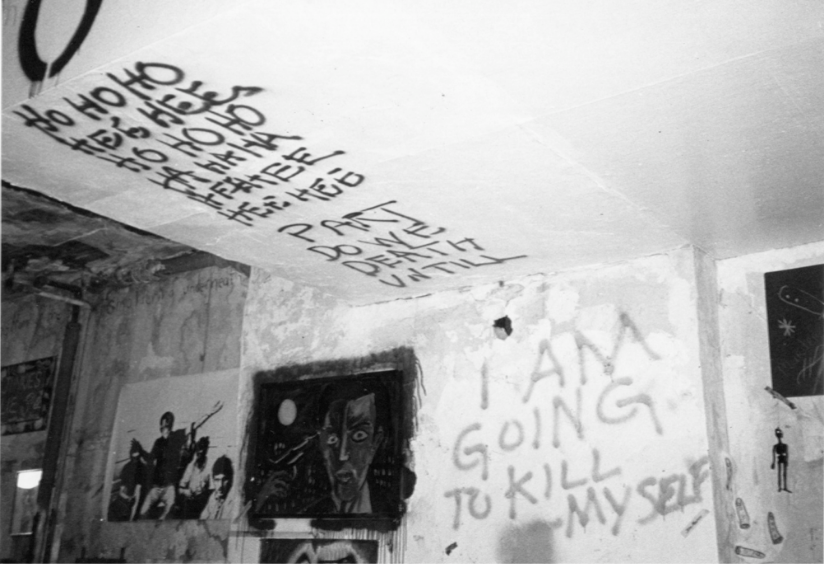

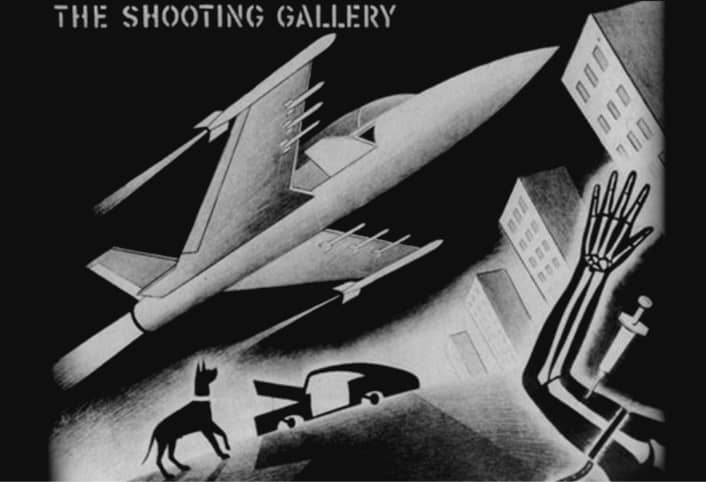

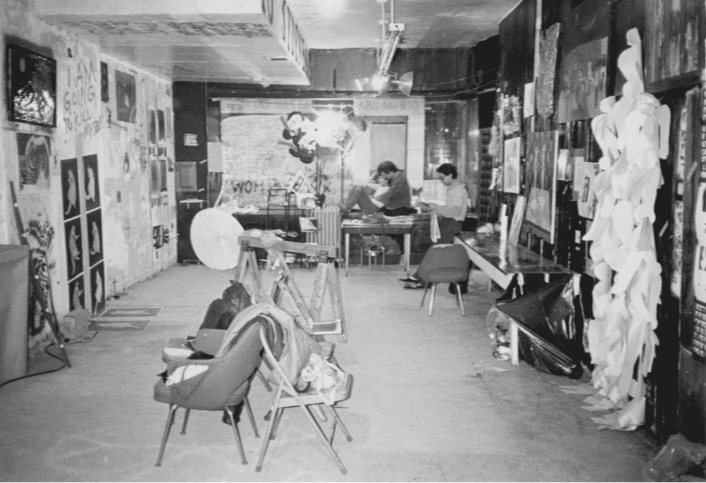

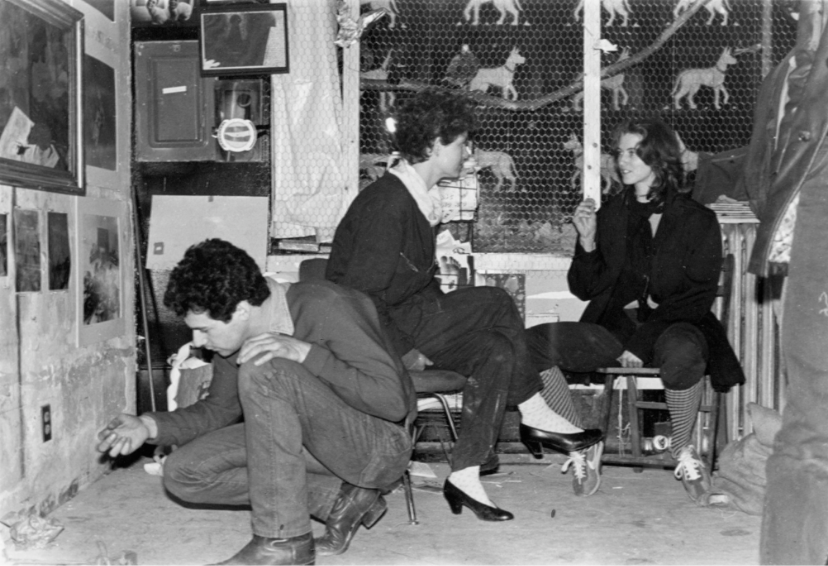

A COMMUNITY OF ARTISTS IN SEARCH OF COMMUNITY

Anton Van Dalen’s dog decals also made it to the storefront window at ABC No Rio in its first year of occupancy at 156 Rivington Street. This neighborhood, home to a working-class Puerto Rican, Dominican, and African American community, had felt the impact of unemployment, drugs, and violence; by the ‘80s only the poorest families remained. Only a few bodegas, street vendors, and domino players populated what had once been lively commercial and residential streets. For the artists at ABC No Rio, disinvestment by the city and the general instability within the neighborhood provided a challenging but potentially fertile ground for the development of anarchist practices. Ad hoc, themed shows juxtaposed rough punk realism with the building’s deteriorating walls and ceilings.

![Installation view shows by Ralph McRae, painting by Richard Bosman, and graffiti by John Morton. Photograph by Tom Warren.]()

![]()

![Murder, Junk, and Suicide Show, 1980. Tom Warren / Anton Van Dalen, ABC No Rio No Dinero.]()

Early shows like Christy Rupp’s Animals Living in the City (1980) envisioned inclusivity without hierarchy: Work contributed by artists, scientists, and school children shared the long gallery space. The idea of a citizen’s center found traction with the neighborhood’s children, but engaging the adult population, who were often preoccupied with survival and perhaps mistrustful of white, middle-class artists moving into their neighborhood, proved harder to engage. Despite good intentions, the projects at ABC No Rio struggled to bridge the social divide between the artists and the other residents of Loisaida.

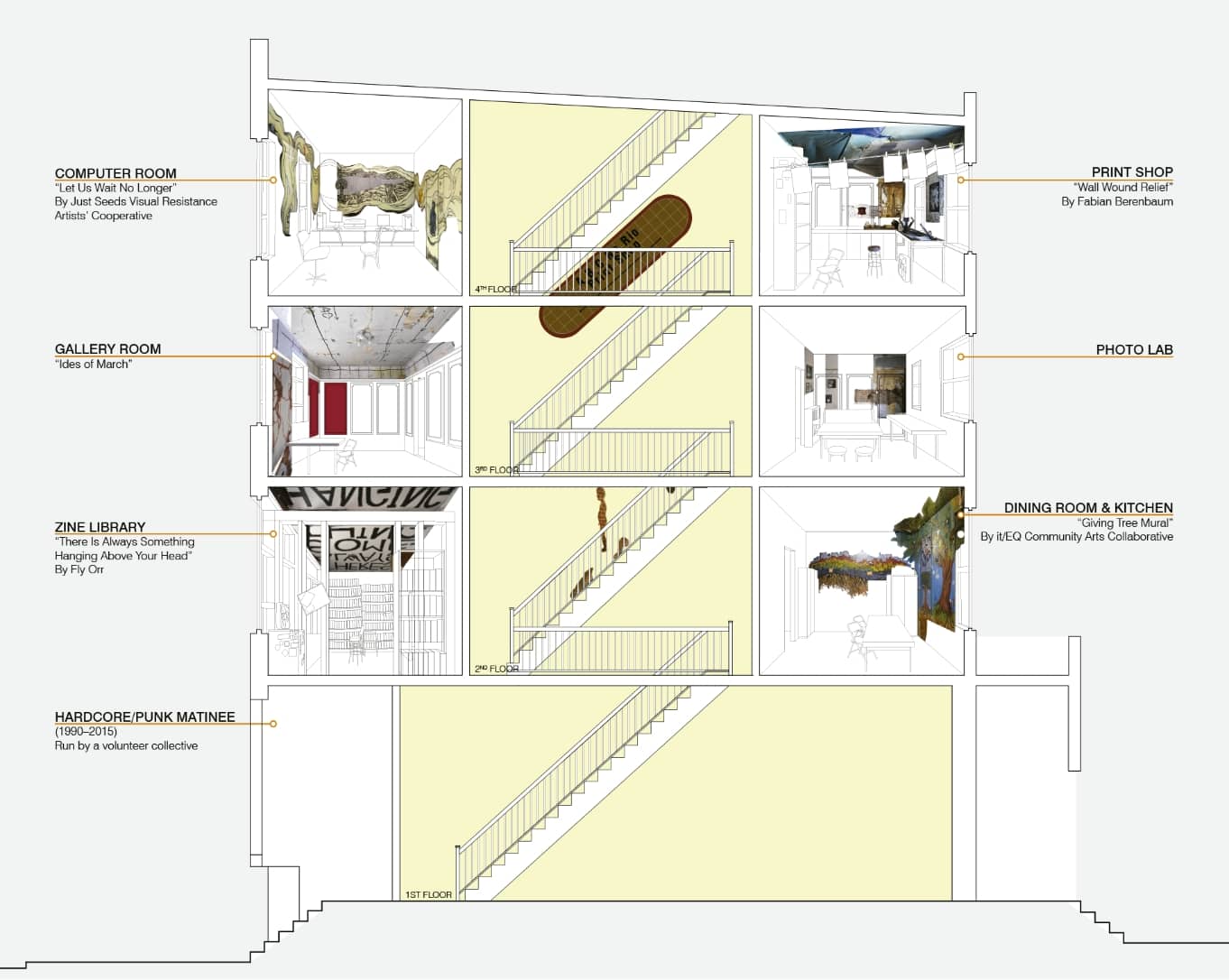

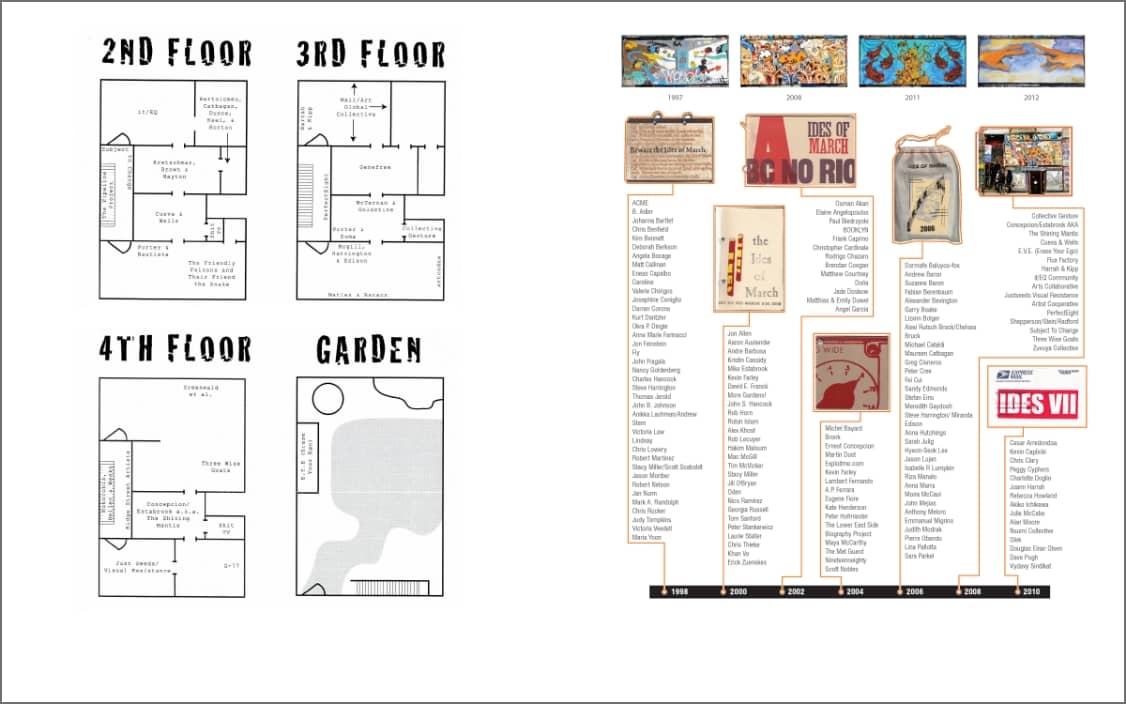

BARN RAISING AND IDES OF MARCH

In the inclusionary tradition of ABC No Rio, the visual arts collective organized a non-juried show in 1998. 61 artists participated in The Ides of March, installing their works throughout the building, on the roof, and in the backyard. The first-floor gallery — the originally leased storefront — remained empty in order to draw visitors up the stairs and through the apartments, into the most domestic reached of the tenement, where they could discover works hidden in closets, lurking inside the broken plaster walls, and hanging from the ceiling of a former bedroom. The Ides of March became a biennial event exhibiting works with nuanced connections to the building itself.

The building became a living archive of all these multifaceted undertakings. Artwork from past shows often remained on the interior stairwell, landings, and rooms within the building. Exploring themes of eviction, dispossession, and the right to space, the drawings, paintings, and reliefs that encrusted the walls evoked the building’s exposed guts. Old symbols acquired new meanings as the political landscape of the country and the urban landscape of the city changed.

Section through ABC No Rio showing wall murals in select room locations, 2015.

Illustration by Nandini Bagchee.

A decade-long effort to keep ABC No Rio open saw a multifaceted movement of street protests, squatting, and petitioning. The varied tactics of the renegade artists and their supporters proved effective. In 1997, the city stopped eviction proceedings and agreed to transfer the ownership of the Rivington Street building to the collective, provided they could raise funds and transform the building into a community gallery.

After the extended battle for possession, the building was the worse for wear. Under a new agreement with the city, ABC No Rio staged a series of open meetings to discuss and shape the institution’s future. What emerged were a series of collective efforts working room by room to transform the building from the inside out.

The bathroom was repurposed as a darkroom, and a computer lab, screen print shop, and zine library were introduced within the different apartments. Organizers of the ongoing Food Not Bombs project cooked out of the surviving kitchen on the second floor, and the resilient HC/ Punk Matinee moved out of the basement to the storefront.